- 2 August 2022

It’s already been a year since the life-saving role of defibrillators was brought into sharp focus when Christian Eriksen collapsed after a cardiac arrest during Euro 2020, prompting an outpouring of concern across the football community and further afield.

After remaining technically dead for 5 minutes, the combination of CPR and the use of a defibrillator saved his life, meaning he was conscious by the time he was carried off the pitch. Since, he has made his miracle debut for his new club at Brentford just eight months after his collapse and has recently joined Manchester United FC on a three-year deal.

What are Defibrillators?

Defibrillators are devices which give an electric shock to the heart of someone who is in cardiac arrest, via pads or paddles applied to the chest. This shock, called defibrillation or ‘defib’, can help to restore the heart’s rhythm.

In fact, they are the ONLY devices that can help when someone has a cardiac arrest. With the effective and speedy delivery of treatment, survival can be raised to 70 percent, but this requires CPR (chest compressions) and also use of a defibrillator.

CPR consists of chest compressions and rescue breaths. These actions are what pumps blood and oxygen around the body. When the brain is deprived of oxygen, a patient will die within minutes, so it’s vital that you start CPR as quickly as possible when someone is in cardiac arrest.

Why Footballers?

Sudden cardiac arrest can occur where a player has an underlying heart condition and while most problems are picked up through screening, a small percentage may go undetected.

The amount of games a professional football player must play in any given season is far greater today than it was at the turn of the century and because of this, Footballers train harder than ever before, meaning they push their bodies, and their hearts, to the limit on a regular basis. Even though the occurrences are rare, young and fit athletes are certainly not immune to heart problems.

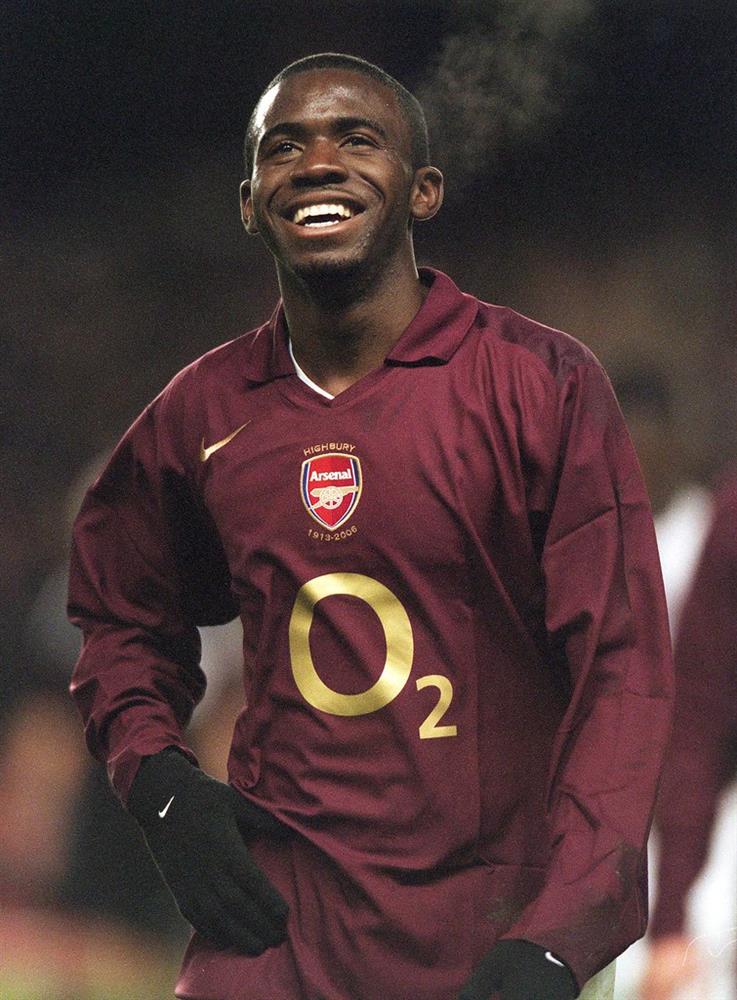

Players suffering cardiac arrest is not a new problem. Former West Ham and Manchester City midfielder, Marc-Vivien Foe, died at 28 while playing for Cameroon in 2003 and ex-Newcastle United midfielder Cheick Tiote collapsed and died aged 30, while training with the Beijing Enterprises Group in 2017.

It is also not only elite players, who are affected. In September, 17-year-old Dylan Rich, a popular and talented left-winger for West Bridgford Colts, died after a suspected cardiac arrest during an FA Youth Cup game in Nottinghamshire.

In most cases, the athletes have an underlying heart abnormality that may have been inherited or remain undiagnosed, where exercise likely acts as a trigger. And the intensity of the exercise may make that heart particularly vulnerable to an arrhythmia that can cause a deadly outcome.

People who are at high risk of sudden cardiac death may be offered an ICD (Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator) which can rapidly treat ventricular arrhythmias – such as Eriksen as well as current Netherlands defender Daley Blind, who has had a cardiac implant since 2019.

Heart Screening:

Cardiac screening includes a range of tests that can assess your risk of heart disease or detect the earliest signs that something isn’t right. Anyone can benefit from heart screening, but it is particularly important for those involved in strenuous exercise.

Sport itself does not cause young sudden cardiac death but it can significantly exacerbate an underlying condition. Professor Guido Pieles, who leads the Sports Cardiology Clinic at the Institute of Sport, Exercise and Health, said there was no evidence that heart problems were occurring in footballers more frequently and he believes any cluster of incidents is a ‘coincidence’. (Walker, 2021)

‘I don’t think we can say this is suddenly increasing, I don’t think it is increasing particularly in football. Footballers are certainly not the athletes that have the highest volume and intensity of training. Endurance runners, Tour de France cyclists, and rowers they train much longer hours…The game has got faster but also people are fitter. If you play football in the Premier League, you have done this since seven or eight years old.’ (Walker, 2021)

However, the expert suggests footballers, and elite athletes, should undergo cardiac screening more regularly throughout their career to give them the best possible protection. ‘The evidence says players aged 15 or16 should be screened because the highest incidence of sudden cardiac arrest is 16-18,’ said the cardiologist. ‘But I do believe we need to do it more often. Players in their twenties need to be screened…Diseases can occur within the 20 years of a player’s career. There should be intermittent screening.’ (Walker, 2021)

Noteworthy cases:

This link between high performance footballers and cardiac arrest has come under increasing media scrutiny. Eriksen’s story, while thankfully having a lucky escape, certainly isn’t the first of its kind in a high-profile football match, with a number of well published incidents such as the deaths of Marc Vivien Foe, Junior Dian, Danny Wilkinson – and the collapse of Fabrice Muamba in 2012.

Today, it seems, the world is paying greater attention to the welfare of footballers; we no longer just view these elite athletes as performers or celebrities. They are human beings; they bleed just like us, and, sadly, they die just like us, too—sometimes prematurely, and sometimes tragically.

Fabrica Muamba

In 2012, Bolton Wanderers star Fabrice Muamba, aged just 23, suffered a cardiac arrest and collapsed during the first half of an FA Cup quarter-final match between Bolton and Tottenham Hotspur at White Hart Lane when his heart had stopped for 78 minutes. Remarkably, Muamba made a full recovery. He was given 28 defibrillator shocks in total, alongside crucially timed CPR. He later retired from the game the following August, under advice from his medical team. He has since spent time being a pundit, studied for a degree in sports journalism at Staffordshire University and as of 2018, also undertaken coaching too at Rochdale with the club’s under-16.

Fabrice and his wife have three sons – Joshua, now 13, Matthew, eight, and five-year-old Gabriel – and daughter Zuri, born in November 2020. The boys have been scouted by Liverpool FC, but the couple have made the tough decision to pull them out, after learning all three have inherited the gene that caused Fabrice to develop hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition where part of the heart muscle grows thicker.

Abdelhak Nouri

Former Ajax Amsterdam player Nouri suffered a cardiac arrhythmia during a pre-season friendly vs Werder Bremen, being revived on the pitch and airlifted to hospital. However, he was left with brain damage and in a vegetative state, and only now has he woken from a coma – two years and nine months after the tragic incident.

Ajax were later forced to admit that their on-field treatment of the player was inadequate, with the Royal Dutch Football Association’s arbitration panel stating his brain damage was a result of Nouri not being resuscitated quickly enough. Club doctor Don de Winter was fired.

Winter is believed to have deviated from UEFA’s guidelines, beginning resuscitation attempts too late. Ajax Chief Executive Edwin van der Sar said at the time a defibrillator should “have been used sooner”.

Marc-Vivien Foe

The footballing world was left shocked by the death of Marc-Vivien Foe, who had been a top player in Ligue 1 with Lens and Lyon, while also a Premier League regular with West Ham and Manchester City, with whom he had been on loan in the months before his passing.

Playing in the Confederations Cup semi-final for Cameroon against Colombia, he collapsed in the 72nd minute with no-one near him. Attempts to resuscitate him failed and he died in the medical centre of Lyon’s Stade Gerland.

An autopsy showed evidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a hereditary condition that increases the risk of death during exertion.

.

Ugo Ehiogu

Tottenham Hotspur’s under-23 coach Ugo Ehiogu sadly died at the age of 44 after suffering a cardiac arrest at Tottenham’s training centre in 2017. Staff at the grounds rushed to his aid to carry out CPR and used a defibrillator kept on site, and his heart started beating again before he was taken to Middlesex Hospital. Despite the heroic effects of the medical team to save Ugo, he died less than 12 hours later on April 21, 2017.

Ugo’s devastated family later discovered he had cardiomyopathy, which is a disease of the heart muscle that makes it harder for the heart to pump blood to the rest of the body.

This ultimately led to his fatal cardiac arrest.

Conclusion:

The level of awareness and provisions in recent seasons is at the highest it’s ever been, which is certainly what benefited Christian in Copenhagen that night — the level of medical support that’s actually in the stadium, as well as his own captain being competent in recognising what needed to be done.

Essentially, the more provision and the more education that society can do on sudden cardiac arrest, the better outcome for not just football players, but everyone.

In need in of a defibrillator? Check out our range of defibrillators today and make sure your organisation is equipped with an onsite AED to keep your team heart safe here!